Richard Ginn likely does not have any descendants, though I cannot rule it out. But although I am not sure I would have liked the man, the fact is that he gives us an interesting story about what life was like for the journeyman craftsman in the London of the early 1700s.

If we think of the early 1700s at all, we think of Pirates of the Caribbean and Dick Turpin. A somewhat romantic view. The reality is told in Hogarth's engravings. London in the period is realistically portrayed by him and by Ned Ward in his "The London Spy" of 1703.

Night- by Hogarth

The real London of the period was one of narrow streets, alleys and courts with quaint names such as Cow-Piss Alley. Filled with filth and disease and a population living on top of one another, the inhabitants, of all classes, were very coarse - drinking, fighting, swearing, whoring and mostly dying well before their time if they survived infancy in the first place. The poor, and there were plenty of those, were often stealing, breaking and entering, murdering and ending up having their necks stretched on Tyburn Hill. Some as Ned Ward tells us, were attempting some escape, by lining up to be taken as indentured servants to the American Plantations - "white slaves" as Ned called them with contempt, signing up to a life of misery. If you believe any of this to be exaggerated, then the story of Richard Ginn dispels any doubts.

Richard Ginn was born in about 1685, the actual baptism does not seem to have survived although it may simply not be online. His parents were Richard and Elizabeth (nee Clark) his father being a Miller of Newmarket in Cambridgeshire. There is a very slim chance that he connects to Hertfordshire (Richard and Ben Ginn/Genn of Ely having a haberdashery shop in Newmarket at the time he was born) but more likely he almost certainly connects to the Ginn family of nearby Burrough Green.

The records of the Coachmakers Company (Guild) of the City of London were totally destroyed in a German air raid in WW2, but by some miracle the apprenticeship records had been indexed, if not the records of those finishing their training and being admitted to the Company.

Richard Ginn was apprenticed for seven years to a Charles Moore of the Coachmakers Company in 1700. As the Company records do not survive I cannot find anything on Chas, but he obviously carried out his trade in central London.

Richard would have completed his apprenticeship and become a Freeman of the Company in 1707. In that same year Richard married an Ann Kesdart (of foreign extraction I suspect) in a clandestine marriage at the Fleet.

Richard and Ann initially lived in Knaves Acre, St James Piccadilly, which Strype described in 1720 as "Knaves Acre or Poultney Street" which he thought long and narrow and "chiefly inhabited by those selling old goods, and glass bottles".

Richard and Ann had their three children there, either Ann was older or they somehow planned their family, because there were only ever three kids.

In the 1720s the couple moved to Parker's Lane in St Giles in the Fields. We know this, because Richard tells us. It was probably something to do with his employer (see below) being appointed the Royal Coachmaker in 1727.

Now, Strype called Parker's Lane long and narrow also, he did not consider it of much account - it ran off of Drury Lane and parallel to Great Queen Street. I was astonished to discover it still does, it is now called Parker Street, how many, if any of the old buildings survive I have no idea.

Richard Ginn was working for a "Mr Birtworth" in the Old Bailey records as transcribed, the King's Coachmaker, but an Australian correspondent who read this post has kindly pointed out that Richard's employer was a Timothy Budworth, who was appointed the Royal Coachmaker in 1727, had his business in St Giles in the Fields and his premises in Parker's Lane no less. Dick was obviously living by the works. Budworth died in 1742 and a Richard Budworth, I assume his son, took over the business and continued the Royal connection.

In the January of 1730, Ann died. She must have been about 50. Scarcely a month elapsed (to the obvious disgust of his son Tom) when Richard remarried an Elizabeth Canis at St Giles, the church was being rebuilt at this time.

Tom Ginn was 13 and he went off the rails. He was up before the Old Bailey - below

Tom got off, but he was obviously not a happy lad, the robbery was in February 1730, his dad remarrying in March. It is likely that the accused dropped the charges.

Whatever the reason, whatever the excuse, Richard Ginn packed his son off to the American colonies as we shall see below.

Richard and Elizabeth did not have any children and from the information we have Liz did not bring any with her from a previous marriage. So by the end of 1730 there was just the two of them.

But Dick had a three storey house, I assume he owned it although the Land Tax records have maddeningly not survived for St Giles. But it seems to have been a narrow but tall house.

They started to take in lodgers. St Giles was apparently famous for it's lodging houses, gin shops and houses of ill repute ie brothels (of which more later) and Dick had two spare bedrooms. By 1733 one was occupied by a Mr Oliver, a young chap, and later a Robert Jasper came to lodge (who shared both a room and a bed - this was common at the time) with Oliver. Later, after 1740, a Richard Baker came to stay. He was a clerk at a Writing Office, apparently like a legal or solicitor's clerk, drawing up documents. He clearly earned more than Oliver and Jasper, and had his own room two steps down the stairs from them. So by 1741 we have three young chaps lodging with Dick and Liz. Elizabeth did not cook for them, this was not a lodging house, like in the time of Dickens a century later, the lads would eat at the local inns and pie shops.

Richard Baker was allegedly (he denied it but the jury did not believe him) a regular visitor to the house of a Mr South in Horsfords Alley nearby, the "White Horse" alehouse in Drum Alley off of Drury Lane (his "local") and the "Coach and Horses" in Drury Lane.

He reputedly used to hang out with a bunch of Irish petty criminals and ruffians at the "White Horse" and pass some time at South's which was "a common receptacle for lewd women" and in the words of one Mary Swinney who was out of work and "lodged" there - "everybody is welcome to come for 3d a piece.." A high class establishment then. The Irish lads turned up at South's every Thursday.

Now, the Irish gang associated with and were known criminals, and in February 1741, one Robert Rhodes, the Constable for St Giles attempted to arrest a chap called Robinson for an offence. He had been looking for him for some time. The Irish (ringleaders Molloy and Timms with perhaps a dozen others), and Dick Baker were at South's (it was a Thursday) and upon hearing of the attempted arrest of their mate the Irish picked up everything they could find, brooms, sticks, mops ("mop handed" rather than "mob handed" then) and rushed to Robinson's assistance. Dick Baker was swept up in the rush.

They beat up Rhodes quite severely, freed Robinson and made a run for it. Some of the Irish chose to rob Rhodes, that was, literally, their fatal mistake.

Some of them were taken quite quickly and the ringleaders hanged after a quick trial. It appears that they had been adventurers, travelling over the continent, in the army, petty crime - you name it. They roamed too far for any genealogist's liking !

Some of the Irish fled back to Ireland. But they caught Dick Baker. There were witnesses against him

Dick denied all and called various people in his defence. Some for good character but nobody who could really convince anybody he was not there.. But he called Richard and Elizabeth Ginn for an alibi, together with Robert Jasper. It was all a lie. they may have felt sorry for him, they scarcely knew him, he may have paid them. I have no idea.

The Ginns claimed that Jasper had been ill for two weeks at the relevant time and that on the night in question Baker had looked after him and asked Liz about cooking Jasper some flounders - Bob cannot have been that ill then it seemed to me, or the jury. Richard Ginn, who left home at 5.30 am and returned at 8.30 pm, six days a week apparently, said that nobody could have got out that night after 9, or indeed any night, because he locked up tight "for I could be killed as well as another man" at 9pm and he had a "vermin" (dog) who let rip at anybody coming in or out (and we all know dogs like that).

The problem was that whilst Richard Ginn said that "his people" were always a abed at 9, Dick Baker's employer and his fellow clerk said that he often worked until midnight, sometimes through the night for an urgent job and his alibi was shot down in flames.

They sentenced him to death. For nearly a month Richard Baker prepared to meet his maker and then the night before his execution at Tyburn -this happened. Lucky lad.

Richard Ginn died in 1743, he was about 58 I would say. He left a will (PCC - National Archives) leaving all to Elizabeth who married John Rolleston, a Confectioner, at the Fleet that same year.

St Giles in the Fields

Richard and Ann had three children:

Richard - was born in 1708. There is no record of an infant death, but that is not necessarily conclusive and there is no apprenticeship record which I would have expected.. There are two suspects for him in the records in later life, but though both married neither had issue. Conclusive evidence linking one of them might turn up.

Ann - was born in 1711.There is no marriage I can trace that might be her and she is not mentioned in her father's will. I suspect she died in infancy.

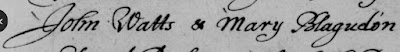

Thomas - was born in 1716 and has intrigued me for years. Note the old Bailey record above. His "punishment" for that episode and the trouble he was clearly giving his father was to be sent as an indentured servant to Maryland in the American colonies in 1730. He was 14 and not the 16 his father claimed. I have seen the original record, but see the summary below from "A list of Immigrants from England to America" - Kaminkow. I am working on it.